Throughout my native plant journey, I have found that articles and education about native plants are often written for professionals and need to be translated to be of use to the home gardener. This winter I learned all over again that this is necessary, certainly for this home gardener, when planning for a new meadow to be installed this spring.

I’ve mentioned before about the Upper Field part of the property. Three years ago, this 8,000 square foot section was engulfed with a tangle of bittersweet and porcelain berry. Since then, I have worked with the good folks at Crawford Land Management to restore the section, first by using backhoes and other heavy equipment to tear out the vines and as many roots as possible. They then put out grass seed and I had it mowed for two years, to ensure the invasives were under control. There are still a few vines that emerge, but I cut and treat them each fall.

Last spring, I decided to start replanting, and worked with Crawford to install 15 native trees – oaks, hollies, red cedars, and pitch pine – and some arrowwood viburnum and beach plums.

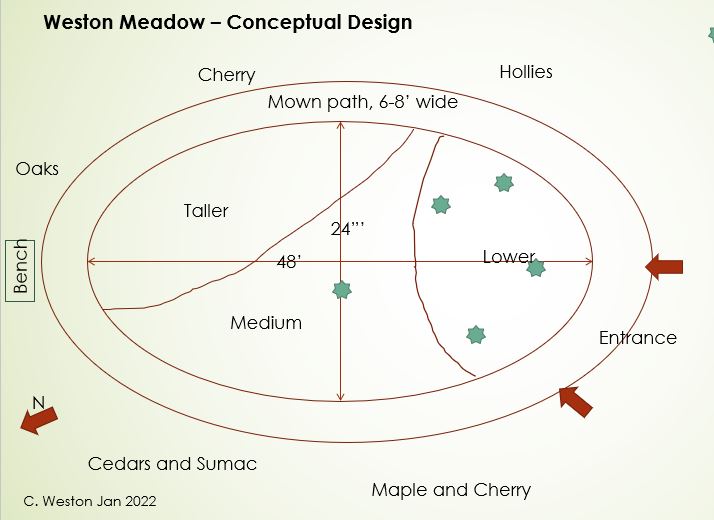

We positioned the trees so there was a large open area in the center, which is the space for the new 1200-square-foot meadow, surrounding the beach plum shrubs. It is intended to be highly attractive for pollinators, butterflies, and moths, adding substantially to their food supply and host plant availability, and it will be pleasant for people to look at too, with a new bench on the uphill side. I started with this as the conceptual design – note that it is not level, but on a slope.

Over the years I have read multiple articles about meadows, taken a class, worked on the meadow on the Rose Kennedy Greenway, and studied the chapters on meadows in my favorite ecological gardening books, and I have even planted a quasi-meadow for the Mayo House in Chatham, so I had a general idea what I was getting into. Nevertheless, I dived back into my books again, and extracted the key points that I, a home gardener, needed to know to tackle this project.

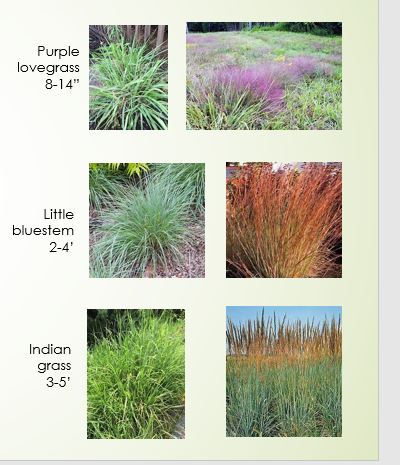

First, meadows in New England are a different breed than the Midwest meadows so often featured in books and articles. They are comprised of the same kinds of plants – mostly grasses interwoven with herbaceous plants. But natural conditions, especially here on Cape Cod support only limited spots where native meadows flourish. The Massachusetts Natural Community Fact Sheets (at www.mass.gov) list only a few – Wet Meadow, Sandplain Grassland, and Sandplain Heathland. The Sandplain Grassland is closest to my conditions – mostly sandy and low-nutrient soil, with dry conditions in full sun. In my designed meadow, I would do well to model it after the Sandplain Grassland, which means sticking to tried and true native grass species as the base – little bluestem, purple lovegrass, and Indian grass.

Second, selecting herbaceous plants for a meadow is trickier than for a normal garden bed. Meadow flowers are generally those that will grow between the clumps of grasses, so they are single-stem plants, not plants that form clumps. Also, plant longevity and competition need to be considered, as does having plants that serve different needs for different pollinators. The best advice I read was from Larry Weaner’s book Garden Revolution, where he advised assembling a mix of short-lived and long-lived plants, ones that bloom at different times of the season, and that have different types and shapes of flowers.

Fortunately, there are also resources that focus specifically on meadows in New England. Professor Cathy Neal at the University of New Hampshire has a wonderful set of resources and plant lists for meadows. Neil Diboll, one of the industry’s leading meadow specialists in the Midwest, wrote a helpful article on New England native plants that can be used in meadows. And the Native Plant Trust’s Plant Finder has a filter for meadow plants. By combining the recommended plant lists, then eliminating those that will not thrive in my sandy dry soil, and trying to balance our longevity, bloom time, and flower shape, I created a plant palette that I reviewed with the folks at Crawford. They recommended some adjustments, and this is the latest version.

Third, meadows cannot be planted in an existing lawn. Lawn grass spreads via runners and will develop sod, a dense mat that will out-compete any flowering plant. Meadow grasses are the types that form distinct clumps, that may grow larger over time, but they reproduce by seed and never form dense mats.

So the grass that had been holding back the vines from reemerging has to go. I consulted with Crawford, and we discussed three different ways to remove it. The one the professionals use most often is treatment with herbicides. This is fast and effective, and their assessment is that this one-time use of herbicide is a reasonable tradeoff to get all the ecological benefits of a meadow. The other two methods avoid herbicide – one is bringing in a sod cutter and removing the sod mechanically, and the other is smothering the grass for an entire growing season with landscaping fabric, cardboard, or other barrier. I’m opting for the sod cutter approach.

Finally, not only are there ecological considerations, there are aesthetic ones. It turns out you can have very different looks to your meadow, depending on whether you arrange your species randomly or in drifts and patches, and how you scatter the shrubs. Here are two examples:

I am going more for the first one – patches and drifts. I spent several fun winter afternoons, plotting out ways to space out the patches so there are three or more patches of each species, so the eye can move around to follow the blooms. I’m also arranging things so that the lower plants are generally on the downhill end of the meadow, and the taller ones are on the uphill side, to emphasize the slope. This is a rough visualization – doing the design simultaneously with pencil on graph paper and with pictures on a screen has been a good approach for me.

Getting this installed will be my one big project for the spring, and I will write more later about sourcing the plants, soil preparation, planting and seeding, watering, and rabbit protection. In the meanwhile, with my planning done, I am enjoying the anticipation!

Looking forward to seeing it! Great article. Very helpful.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a wonderful winter project you had! Thank you for pointing us to resources that could be used in our own projects. Is it true that most meadow plants do best in full sun?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Alanna, glad you enjoyed the article! Yes, meadow plants are all full-sun plants, which would mean at least 6 hours of direct sun every day. Cathy

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s a BIG project! And exciting. Love your choice of patches rather than drifts. Do you need to amend the soil before planting?

LikeLike

[…] reality, isn’t it? Over the last month, with some great help, the meadow has been planted! Here’s a reminder of the plans, with the layout and the detailed plant […]

LikeLike