If you have been reading this for a while, you know I have been installing native plants to support pollinators for years. At last count, the property has over 100 species of native trees, shrubs, perennials, ferns, and grasses, and the observed numbers of insects have increased noticeably.

But still there has been little real science behind the details of what I have planted, just a general understanding that pollinators require native plants to survive, so I have planted a variety and hoped for the best. This feels a bit like throwing spaghetti against a wall and hoping something sticks. So, I have been keeping an eye out for resources that might help refine my approach and do even more, especially for pollinators most at risk.

I found an excellent resource recently when I attended a webinar put on by the Ecological Landscape Alliance , in a presentation called Pollinate Now, by Evan Abramson of Landscape Interactions.

The presentation describes a report that Landscape Interactions has published that is a combination of research and demonstration project, and that brings in-depth science to the process of planting to support at-risk pollinators. The project focuses on the lower Hudson River Estuary watershed in New York, but there is supposed to be a high overlap with other Northeast regions, so it should provide guidance here on Cape Cod. Here, I’m going to summarize the report and presentation, but the full report is available for download at Landscape Interactions.

This post is my summary of the full report, and it is long and full of information, so please bear with me. Note that all illustrations and quotes are from the report, while all opinions and the summaries of the findings and conclusions are mine, based on the report. Mr. Abramson has kindly given permission to use his material in this post and has reviewed it for accuracy.

A Case for Supporting Pollinators

The Pollinate Now report builds one of the strongest cases I’ve seen for supporting pollinators. The researchers consolidated a wide variety of available studies to assess the state of pollinators in the lower Hudson River Estuary watershed. Their key points in their case are based on the findings of their research:

- Resiliency in our threatened climate situation requires a high level of biodiversity in plants, insects, and wildlife, so that as some species are threatened, others can fill in the gaps.

- Biodiversity requires a strong food web, and the base of the food web is the pollinator-plant interaction, the only way the energy plants make from sunlight and water can be transferred into higher points of the food web. Pollinators are therefore a keystone element of biodiversity.

- Humans are affected by this too. If you enjoy apples, blueberries, tomatoes, eggplants, or melon, you are relying on native pollinators – specifically, 6 types of native bees.

- Pollinators are in significant decline. The research identified 95 target species of bees, butterflies, and moths, species that have been present in that region in the past and should be there today. However, they found that “between 38% and 60% of New York’s native pollinator species are at risk of extirpation and 15% have not been seen since before the year 2000. For bees, up to 24% of species are at risk and 11% are likely extirpated (White et al., 2022). In total, over half of New York’s native pollinator species are no longer present in the state or may no longer be present within a short period of time, unless some drastic measures are taken.”

- Native bees have a very wide range of nectar and pollen needs as well as nesting requirements. It turns out that if you meet the needs of a variety of native bees, you will meet the needs of many other pollinator taxa, including beetles, wasps, flies and hoverflies.

- Species in decline tend to require more specialized habitats and food sources, i.e. specific native plants. However, “The flora of New York and New England also shows some disturbing trends. At present, one-quarter of the region’s native plant species have been lost in comparison to historical figures, and non-native plant species have increased regionally up to 19.7%.”

- There is some good news: some threatened species are stable or recovering. Honeybees have turned around (and are competing with native bees for resources), and eastern monarch populations are stable (western monarchs are still in decline).

Their conclusion: If we want a healthy and biodiverse environment with all its functional and aesthetic value, we need to support native bees, butterflies, and moths, and we should do so by targeting the needs of at-risk species through building a landscape with plant diversity and abundance.

Demonstrating How to Support Pollinators

The second part of the report focuses on four key types of habitats. For each type, Landscape Interactions collaborated with a local landowner to make their properties part of a long-term demonstration of methods of supporting pollinators. The four habitats are riparian (riverfront), agricultural (fallow fields), urban/residential (area around a YMCA), and conservation (a large privately owned property that is protected from development). For each habitat, they started by conducting a baseline survey of all native bee and butterfly species that were observed feeding at any plant on the site. This was done by four monthly observations across a growing season. The baseline showed a very low number of targeted species, 3 bees and 3 butterflies across all four sites. Clearly there was significant need for resources to attract and support more native species.

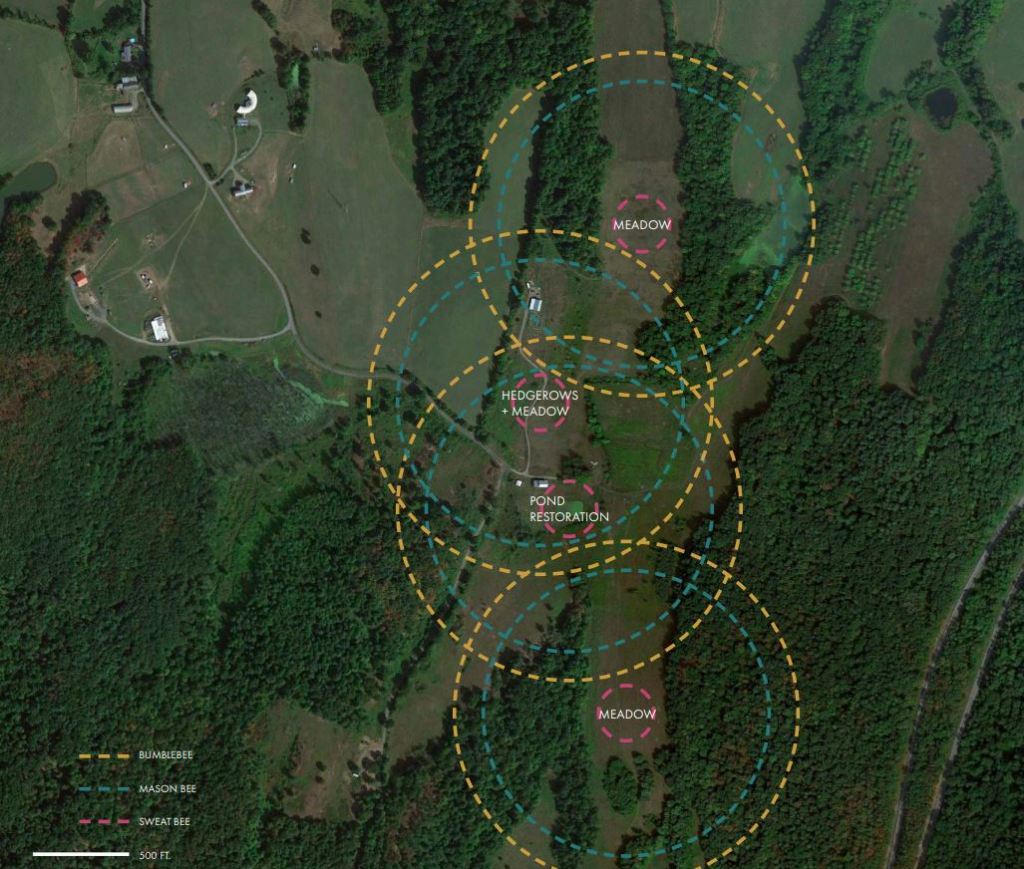

Supporting at-risk pollinators requires ensuring sufficient specific habitats, so one area of the demonstration project focused on creating welcoming habitat areas. As I read this, I realized this is a need that home gardeners like me are seldom aware of. The report provides science to guide us, as well as their project.

- One key factor is habitat connectivity – bee habitats need to be within 100 – 500 feet of their food source. For me, that means I need to plan for habitat near the new meadow.

- In New York, 58% of bees are solitary ground nesting bees, who excavate nests underground. They need bare surface, not covered with grass or mulch, preferably in a sunny, sloped area with sandy soil. I have just the place uphill from the meadow and will make sure that patch remains bare.

- The next group, solitary wood-nesting bees, comprise 19% of bees, and nest in hollow cavities such as stalks of perennials and shrubs (ex: Joe Pye weed, elderberries, raspberries) or in tunnels left over from burrowing insects. To support these bees, leave standing wood and leave perennial and shrub stalks over the winter, and in spring only cut them back to 15-18”.

- The last group are the bumblebees, who are social and need more space, so they nest in old animal burrows, abandoned hay bales, brush piles, birds’ nests and bird houses. With these needs in mind, the researchers designed areas in the four sites that are designated as bee habitats.

The other key need is sources of nectar and pollen. The Pollinate Now group researched the specialized needs of the species most at risk, and compiled a list of about 150 native trees, shrubs, perennials, grasses, sedges, and ferns. For each demonstration site they designed a planting plan using these plants, and in 2024 they installed the native plants on the four sites. The plan is to give the sites two years to become established, and re-measure the pollinators present in 2026 and 2027.

Here is a snippet of the plant list:

Here is an example of the Urban/Residential planting plan. Note that much more detail for each section of this site is included in the report.

Applying This At Home

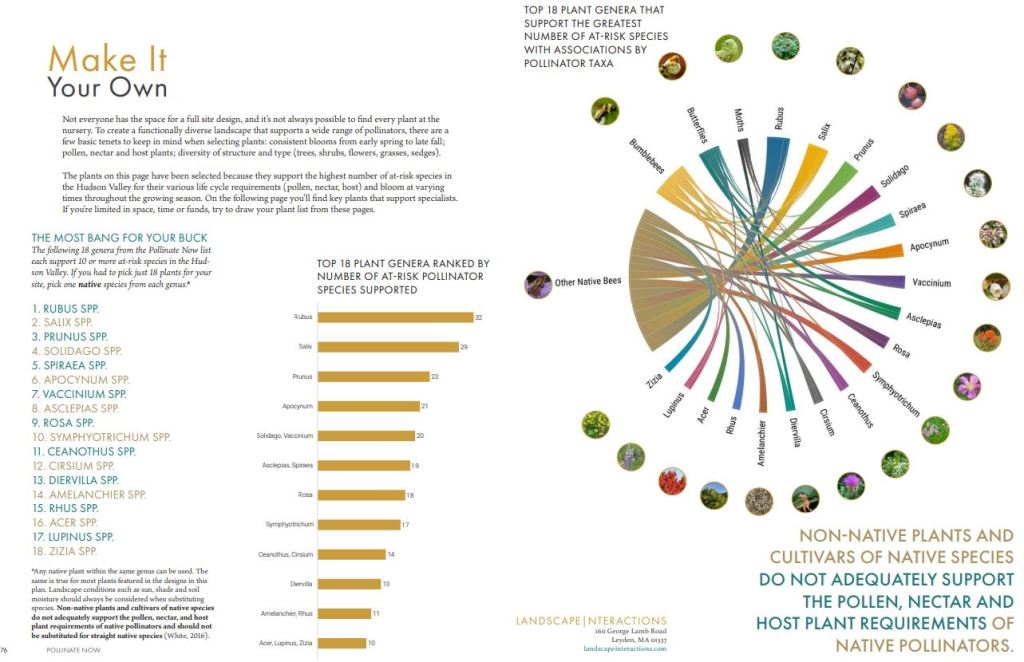

For us home gardeners who lack the science, time, and energy to do comparable research to target which plants we need for our own gardens, the Pollinate Now report goes one step further. They analyzed exactly which plants support which species (I’m envisioning a giant spreadsheet) and then summarized which 18 genera of plants support the highest number of at-risk species.

Can we use these charts and recommendations here on Cape Cod? I think so, as many of the native plant species they identify for the lower Hudson River watershed are key plants here on Cape Cod as well. To bring this closer to home, I used the Native Plant Trust Garden Plant Finder to create the following chart of species within the 18 genera from the Pollinate Now plant list that are native to ecoregion 84, which includes Cape Cod:

| Genus (In order of importance) | Cape Native Species | Common Name |

| Rubus Blackberries, etc. | Rubus allegheniensis | Blackberry |

| R. hispidus | Creeping dewberry | |

| R. idaeus | Red raspberry | |

| R. occidentalis | Black raspberry | |

| R. odoratus | Purple flowering raspberry | |

| Salix Willows | Salix discolor | Pussy willow |

| S. nigra | Black willow | |

| Prunus Cherries and plums | Prunus americana | American plum |

| P. maritima | Beach plum | |

| P. penslyvanica | Pin cherry | |

| P. pumila | Sand cherry, dwarf sand plum | |

| P. serotina | Black cherry | |

| P. virginiana | Chokecherry | |

| Solidago Goldenrods | Solidago caesia | Wreath goldenrod |

| S. flexicaulis | Zig-zag goldenrod | |

| S. nemoralis | Gray goldenrod | |

| S. odora | Sweet goldenrod | |

| S. puberula | Downy goldenrod | |

| S. rugosa | Rough goldenrod | |

| S. sempervirens | Seaside goldenrod | |

| Spirea | Spirea alba | White meadowsweet |

| S. tomentosa | Steeplebush | |

| Apocynum Dogbane | Apocynum androsaemifolium | Spreading dogbane |

| A. cannabinum | Hemp dogbane | |

| Vaccinnium Blueberries | Vaccinium angustifolium | Lowbush blueberry |

| V. corymbosum | Highbush blueberry | |

| V. macrocarpon | Large cranberry | |

| Asclepias Milkweeds | Asclepias exaltata | Poke milkweed |

| A. Incarnata | Swamp milkweed | |

| A. syriaca | Common milkweed | |

| A. tuberosa | Butterfly milkweed | |

| Rosa Roses | Rosa Carolina | Carolina rose |

| R. virginiana | Virginia rose | |

| Symphotricum Asters | Symphotricum cordifolium | Blue wood aster |

| S. leave | Smooth aster | |

| S. novae-angliae | New England aster | |

| S. novi-belgii | New York aster | |

| S. puniceum | Purple-stemmed aster | |

| Ceanothus Redroot | Ceanothus americanus | New Jersey tea |

| Cirsium Thistles | Cirsium discolor | Field thistle |

| C. horridulum | Yellow thistle | |

| C. muticum | Swamp thistle | |

| C. pumilum | Pasture thistle | |

| Diervilla Honeysuckle | Diervilla lonicera | Bush honeysuckle |

| Amelanchier Serviceberry | Amelanchier arborea | Downy serviceberry |

| A. canadensis | Canada serviceberry | |

| A. laevis | Allegheny serviceberry | |

| A. spicata | Running serviceberry | |

| Sumac | Rhus copallinum | Winged sumac |

| R. glabra | Smooth sumac | |

| R. typhina | Staghorn sumac | |

| Acer Maples | Acer pensylvanicum | Striped maple |

| ‘A. rubrum | Red maple | |

| ‘A. saccharinum | Silver maple | |

| ‘A. saccharum | Sugar maple | |

| Lupinus Lupines | Lupinus perennis | Sundial lupine |

| Zizia Golden alexander | Zizia aptera | Heart leaf golden Alexander |

| Z. aurea | Golden alexander |

These 58 plants (of the 350 plants that Native Plant Trusts lists for ecoregion 84) seem likely to be a strong support of our native bees. It is interesting that this list of the top 18 genera for at-risk pollinators, while it includes mostly trees and shrubs, does not include oaks, which Doug Tallamy has shown are critical for supporting caterpillars as well as other insect species. This tells me that having oaks and a variety of plants from the Pollinate Now list should increase pollinator support across the board.

While this report is definitely helpful, we still have the questions of exactly what species of pollinators we have on Cape Cod, which are at risk, and whether some different native plant species would support them. I plan to keep an eye out for similar studies focused on Cape Cod.

My big takeaway from this science is that over the winter I need to do a thorough assessment of my support for native pollinators – whether I have enough habitat, and enough of the right plants. I do have some opportunity to add more plants, and this list gives me some welcome guidance for next year’s planting projects.

excellent research and the bottom line list of plants very useful. Thank you!

LikeLike

Good morning!

Thank you for this wonderful summary and plant list. I always enjoy reading your garden updates and I appreciate all the work you’ve put into your plant list. I’m going to share it with some of my master gardener cohort in metrowest Boston.

Best,

Lisa Gianelly

Certified Master Gardener

LikeLike